Wednesday, June 9, 2010

Bio-char skepticism

There is a strong statement against biochar at this site (below). Many objections are raised in the article. It's the first time I had seen such a statement, so I'm sharing it. Biochar seems to be a technological solution - a form of geo-engineering - with possible unintended consequences and costs. It has gained in popularity in the

last year and is being widely advanced in climate analyst and scientific circles.

http://climateandcapitalism.com/

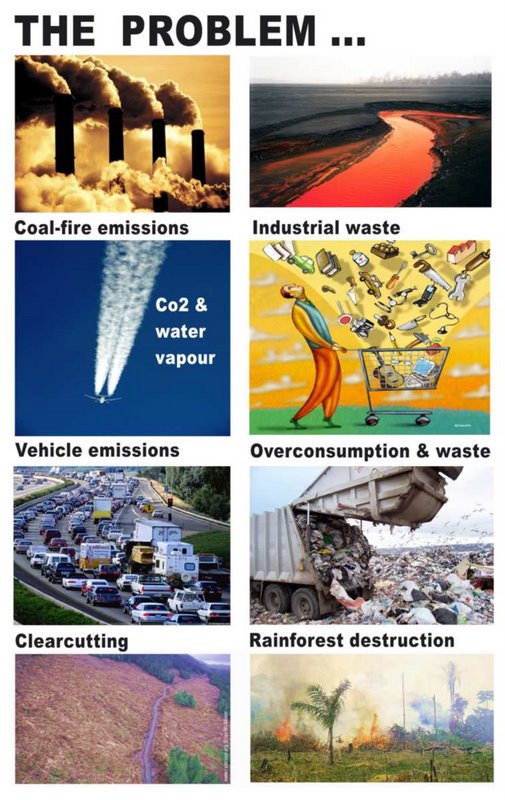

The biochar ideas raises the ethical questions associated with other localized technological solutions: nuclear energy, sulphur particles in the atmosphere, iron filings in the seas, carbon sequestration. Not all these technologies are alike in all respects, but they do share some commonalities. Before I launch into my crtitique, I should add that I do not have the final answers. This is a provisional set of statements. I raised these points for discussion only, because it seems important to do so, and I welcome alternative points of view.

Roughly speaking, these localized technological solutions share these problematic characteristics, which need to be considered prior to their implementation:

1) They have social and environmental costs attached to them, which from a deontological ethical perspective, negates their value. From this perspective it is morally wrong to make x pay the cost for the benefit of y, if x and y are equals. All human beings are equals in this view.

In other words, the rights of individuals and minorities must be upheld and solutions to social or environmental problems must take into account those individual or local community rights. Solutions must be "universalizable." From a deontological perspective, war would not be justifiable, and nor would any development project which imposed burdens on local populations for the sake of the economic prosperity of the larger society.

However, from a utilitarian perspective, which allows for minority populations or individuals to suffer for the good of the greater happiness, such technologies - if they worked - would be considered ethically acceptable. It is this ethic which is being used (implicitly, not explicitly) right now.

The utilitarian perspective will seem practically necessary to many, given how widespread human self-interest and faith in technology appears to be, but it is still morally wrong (in my opinion) for the reasons stated above, and given limited time and resources, climate change mitigation requires the choice of one or the other perspective and set of commitments associated with it.

As I hope to demonstrate in these few paragraphs, the deontological perspective can be (roughly) associated with a no-growth economy and investment in renewables and other intermediate technologies, and the utilitarian perspective can be associated with advocacy for high-tech solutions which have localized costs and which are often used in connection with justifying the current model of unlimited economic growth.

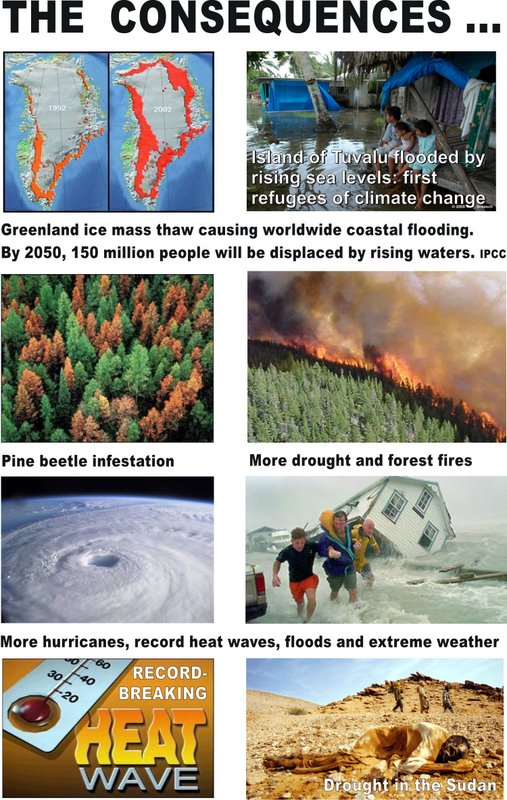

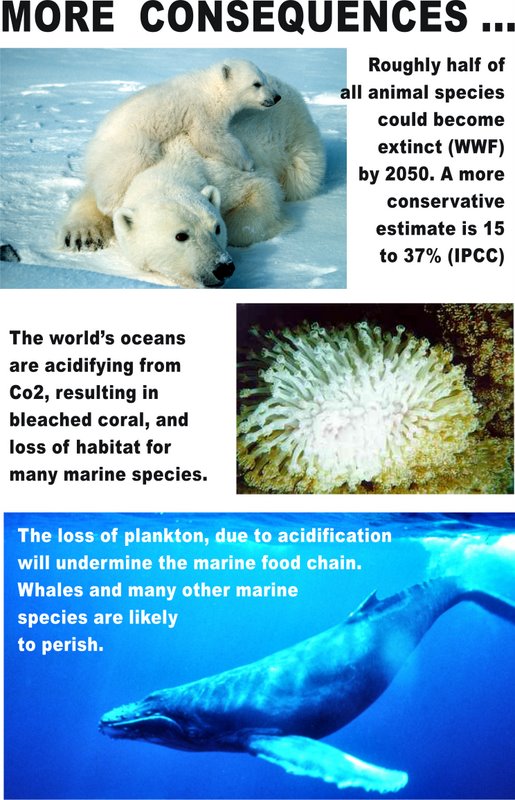

2) There are local consequences that no one can anticipate fully, but advocates for these technologies are advancing them nonetheless as mitigation techniques for climate change. Their use in the world is being advanced as an experiment and local populations and ecoystems are part of that experiment, which raises ethical objections.

The regulatory framework and environmental assessments - if they are applied - be described as utiliarian in their bias, using a risk management methodology. The risks are borne by local populations, often without their consent, and also by future generations, who cannot give their consent.

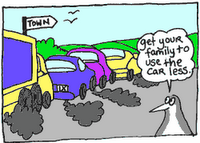

3) Advancing these technological solutions is tantamount to accepting the unsustainable status quo of unlimited economic growth. The "magic buckshot" ethic advanced by many climate policy analysts - which is a mix of existing and experimental technologies - ignores the fact that funds spent on experimental technologies could be better spent on renewables.

The latter (renewables) are associated with energy conservation and widespread behavioral change and are therefore not considered viable of their own, within the context of the economic growth paradigm.

4) There are high financial costs as well attached to them, and in a world of limited funding for climate change mitigation, it is arguable that such funding could be better spent on proven technologies (renewables) where the social and environmental costs are relatively minor. This is especially the case with nuclear energy, but the argument may be applicable to biochar as well, depending on the costs

associated with implementing it on a widespread scale.

From this perspective, it is an either/or scenario, financially: if funds and energies are spent on experimental solutions which potentially would allow the economic growth regime to continue, they take away from relatively low-cost intermediate technology solutions which require greater energy efficiency and behavioral change (a low growth or no growth economy).

The perspective in general use among analysts and polticians right now is that we must try all possible options and see which one works, or which combination of them work, and commit to that. But in the case of nuclear energy and renewables, limited funding spent on one is necessarily not spent on the other. This could also be the case with biochar, depending on how much its implementation on a widespread

scale might cost.

It should also be added that the least expensive option available for mitigating climate change on a large scale is the elimination of factory farms and a severe reduction in meat consumption in industrialized nations which rely on factory farms for food. According to a 2007 U.N. report, 18% of global greenhouse gases from industrial meat production.

last year and is being widely advanced in climate analyst and scientific circles.

http://climateandcapitalism.com/

The biochar ideas raises the ethical questions associated with other localized technological solutions: nuclear energy, sulphur particles in the atmosphere, iron filings in the seas, carbon sequestration. Not all these technologies are alike in all respects, but they do share some commonalities. Before I launch into my crtitique, I should add that I do not have the final answers. This is a provisional set of statements. I raised these points for discussion only, because it seems important to do so, and I welcome alternative points of view.

Roughly speaking, these localized technological solutions share these problematic characteristics, which need to be considered prior to their implementation:

1) They have social and environmental costs attached to them, which from a deontological ethical perspective, negates their value. From this perspective it is morally wrong to make x pay the cost for the benefit of y, if x and y are equals. All human beings are equals in this view.

In other words, the rights of individuals and minorities must be upheld and solutions to social or environmental problems must take into account those individual or local community rights. Solutions must be "universalizable." From a deontological perspective, war would not be justifiable, and nor would any development project which imposed burdens on local populations for the sake of the economic prosperity of the larger society.

However, from a utilitarian perspective, which allows for minority populations or individuals to suffer for the good of the greater happiness, such technologies - if they worked - would be considered ethically acceptable. It is this ethic which is being used (implicitly, not explicitly) right now.

The utilitarian perspective will seem practically necessary to many, given how widespread human self-interest and faith in technology appears to be, but it is still morally wrong (in my opinion) for the reasons stated above, and given limited time and resources, climate change mitigation requires the choice of one or the other perspective and set of commitments associated with it.

As I hope to demonstrate in these few paragraphs, the deontological perspective can be (roughly) associated with a no-growth economy and investment in renewables and other intermediate technologies, and the utilitarian perspective can be associated with advocacy for high-tech solutions which have localized costs and which are often used in connection with justifying the current model of unlimited economic growth.

2) There are local consequences that no one can anticipate fully, but advocates for these technologies are advancing them nonetheless as mitigation techniques for climate change. Their use in the world is being advanced as an experiment and local populations and ecoystems are part of that experiment, which raises ethical objections.

The regulatory framework and environmental assessments - if they are applied - be described as utiliarian in their bias, using a risk management methodology. The risks are borne by local populations, often without their consent, and also by future generations, who cannot give their consent.

3) Advancing these technological solutions is tantamount to accepting the unsustainable status quo of unlimited economic growth. The "magic buckshot" ethic advanced by many climate policy analysts - which is a mix of existing and experimental technologies - ignores the fact that funds spent on experimental technologies could be better spent on renewables.

The latter (renewables) are associated with energy conservation and widespread behavioral change and are therefore not considered viable of their own, within the context of the economic growth paradigm.

4) There are high financial costs as well attached to them, and in a world of limited funding for climate change mitigation, it is arguable that such funding could be better spent on proven technologies (renewables) where the social and environmental costs are relatively minor. This is especially the case with nuclear energy, but the argument may be applicable to biochar as well, depending on the costs

associated with implementing it on a widespread scale.

From this perspective, it is an either/or scenario, financially: if funds and energies are spent on experimental solutions which potentially would allow the economic growth regime to continue, they take away from relatively low-cost intermediate technology solutions which require greater energy efficiency and behavioral change (a low growth or no growth economy).

The perspective in general use among analysts and polticians right now is that we must try all possible options and see which one works, or which combination of them work, and commit to that. But in the case of nuclear energy and renewables, limited funding spent on one is necessarily not spent on the other. This could also be the case with biochar, depending on how much its implementation on a widespread

scale might cost.

It should also be added that the least expensive option available for mitigating climate change on a large scale is the elimination of factory farms and a severe reduction in meat consumption in industrialized nations which rely on factory farms for food. According to a 2007 U.N. report, 18% of global greenhouse gases from industrial meat production.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment